Ethogram of the Pigeon

These ethograms are being shared under the Fair Use Act for the purposes of education. Goodwin’s ethogram will be denoted by the initial G, Johnston’s with a J, and Haag-Wackernagel’s with an H (still being translated).

Disclaimer for Goodwin’s ethogram: The word “Pigeon” with a capital “P” is used throughout for the species C. livia; where any or all other species are meant “pigeon” with a small “p” is used. Though it is usual to capitalize only species names, [Goodwin] ha[s] here used capitals also for different forms of C. livia, thus “Feral Pigeon”, “Step Pouter”, and so on.

SELF MAINTENANCE BEHAVIOR

G: Feeding behavior

Food is sought on the ground, under natural conditions in completely or fairly open areas. Exceptionally, but in some places regularly (Feral Pigeons), berries may be taken from the peripheral branches of trees or shrubs. Pigeons can easily be taught to seek food on ledges, window sills, etc. and it is possible that Rock Pigeons may obtain some food from cliff ledges although their main feeding areas are usually on ground above and often well inland from the cliff tops.

Pigeons may visit their feeding grounds and search for food singly, in pairs, or in small or large flocks but when a distance of half a mile or more separates “home” from the feeding ground and especially where the Pigeons are a risk from birds-of-prey it is usual for a group of birds to leave together and fly fast and direct, usually low over the ground, to the feeding area. Both the ability and inclination for such fast “commuting” flights have been “bred out” of many fancy breeds but are still retained, in appropriate circumstances, by, for example, most Racing Pigeons, and clean-legged varieties of some of the “German Toy” breeds. The tendency of lost or hungry individuals to follow others which fly in a determined manner and to alight where others are already feeding functions in part as a means of finding food.

The Pigeon is primarily a seed eater. A wide variety of seeds are eaten, perhaps especially those of vetches and cultivated grains and pulses when available. Small snails and other invertebrates, of species or at life stages that are slow or immobile are also taken, especially by birds that are feeding young. Green vegetation is sometimes eaten but probably only when the diet is deficient in some elements which it can supply. Some Domestic Pigeons become conditioned into taking large quantities but under normal conditions the species takes little greenfood. Mineral matter, usually containing either calcium or salt, is regularly taken, often in considerable quantities by Pigeons that are feeding young. Tame but free-living Rock, Feral, and Domestic Pigeons that I kept would consume about a dessert spoonful of “Kilpatrick’s Pigeon Minerals” after feeding and before drinking and then going to feed their own young. Free-living Feral Pigeons have been seen to eat crushed snail shell, earth (possibly containing calcium or salts), wet sea sand and salt solution leaking from containers in London streets.

When they begin to feed themselves, young Pigeons peck at small objects that contrast to some degree with the substrate. If movable, these are picked up, held a moment in the bill tip, and then dropped. If some edible seeds are present, the bird will eat them but the first seed eaten is picked up and dropped several times before it is swallowed. If experienced Pigeons are present when the young bird first starts to feed, it shows excited interested when it sees another Pigeon pick up food. The young one goes to it, looks when it pecks again and sometimes tries to take the morsel from the others’ bill tip at the moment that it is picked up. This may be repeated few or many times until, apparently, realization comes to the young bird and it starts to search for, pick up, and swallow food for itself, with much less delay and hesitation over the first morsel that it would have shown if learning to eat alone.

Adult Pigeons confronted with some food new to them behave in a similar manner. Pigeons learn to take new foods of small size, such as wheat, rice, or millet more quickly than larger seeds such as maize, tic beans, or peanuts. This bears no relation to their choices when experienced.

Feral Pigeons in towns often feed largely on human foods such as bread, cake, cooked meats, fried potatoes, and so on. These foods do not bear much resemblance to natural foods and there does not appear to be any innate recognition of them as potential foods as there certainly appears to be in the case of seeds. The example of older, experienced birds seems usually the main factor that induces inexperienced young Pigeons to sample such foods. Obviously, however, some individuals must initially do so on their own initiative. In many towns, there must be intense selection in favor of those Feral Pigeons prepared to sample “unnatural” foods.

The behavior mentioned above, in which a Pigeon picks up a potential but as yet (to it) unknown food object, holds it a moment in the bill tip, drops it, picks it up again, and repeats the process sometimes several times before swallowing it is shown whenever the bird is undecided whether to eat or not. Thus when a satiated Pigeon finishes eating from a supply of food, it will usually pick up, hold a moment, and then drop a few morsels before finally leaving the food. Pigeons appear able to correlate the pleasant or unpleasant after effects of anything eaten with its (remembered?) appearance. Thus a tame bird that has, after much coercion and coaxing on the part of its owner, eaten peanuts for the first time, will after some hours but not usually before, become extremely eager for them.

When searching for food in a loose and easily movable substrate, Pigeons will shift it with a sideways flicking movement of the bill. To pluck a piece of foliage or a seed from a growing plant, the bird closes the bill on it and then tugs. If the seed is not detached by this the pull is followed by a shake of the head as the bird still holds the seed. This is often effective although the shaking movement seems to be an innate reaction to the seed head or other part of the plant touching or nearly touching the bird’s head. Another feeding stratagem is to grasp the food object in the bill tip and then make a shaking movement without lifting the head much or at all so that the object held is rubbed or knocked on the substrate. I have seen this method used to remove elm (Ulmus) seeds from their surrounding “wing” and, together with the shaking with lifted head, to free the cotyledons of fallen and broken acorns from the husk. All these innate movements are also used when in difficulties with such human foods as bread and meat, with which they are often very inefficient.

The present species does not posses the twisting wrench with which the Wood Pigeon (Columba palumbus) and some other arboreal species pluck fruits and acorns.

G: Drinking

The Pigeon drinks by inserting the bill and sucking up a continuous draught of liquid. Immediately after, it lifts its head and slightly expands its gape. One or two more and usually shorter drinks may follow the first. Apart from the pigeon family (in which I do not include the Sandgrouse) only a few other birds regularly drink in this way but some species that normally drink by the more usual method of repeatedly dipping and lifting the head will suck in a pigeon-like manner at times.

Pigeons usually drink after they have fed, before flying back to roost, or feed their young. They may, however, drink before they finish searching for food, if water is easily available at the feeding area. When stressed by heat or thirst, they may drink at any time on an empty crop.

G: Bathing

Pigeons often bathe in rain; the bird leans to one side, often lying partly on one folded wing and raising the other so that rain can fall on its underside. The body feathers are usually erected and the tail partly spread. Often the bird will lean over till the open wing is almost horizontal and the bird almost completely on its side. When a bird does not wish to bathe is caught in the rain, it adopts an upright posture with the neck contracted and all feathers sleeked down to allow the rain to run off.

Pigeons also bathe where shallow water is available at a place where they feel at ease. The bird wades into the water, fluffs out its feathers, makes a few pecking or sideways flicking movements of the bill in the water, then usually remains still for some moments, sometimes with one wing raised as in rain bathing. This quiescent period is followed by and later interspersed with violent ducking of the head and beating the partly opened wings in the water. Finally the bird steps out of the water, stands up or makes a little jump into the air, violently beating its wings, then settles in some safe-seeming and preferably sunny place to dry and preen. When not actively preening it stands or squats with the wings very slightly opened so that the primaries are a little spread.

J: Bathing

Pigeons bathe in water fairly regularly. A shallow puddle may be adequate; a bird wades into water and dips its breast and head in water and by flapping the flexed wings disperses water over its entire surface. Feathers may be erected and depressed, and a good amount of vigorous shaking, creating a watery halo around the bird, is characteristic. Pigeons bathe in rain and (in captivity) may be stimulated by dripping water, sometimes suggesting sun-bathing by lying on their sides in water and vertically extending the free wing, allowing water drops to splash over the underwing surface. Water bathing is for general feather maintenance, removing dust and grit, etc., and possibly also affects feather parasites.

G: Sun-bathing

The rain bathing postures (q.v.) are also used when sunning at high intensity although more often the bird lies slightly on one side with the wing on the other slightly or partly spread and extended and the tail spread on the same side.

On a fine early morning Pigeons (Rock and Feral) commonly spend some time preening and resting in the sun on some ledge or slope of a cliff or building that faces east and is sheltered from the wind, before flying off to seek food.

J: Sunning

Sunning or sun-bathing is undertaken by a bird lying on its side and exposing an entire half of its body to sunlight. The bird may raise a partly flexed wing exposing the underside, or extend it so the dorsal surface receives sunlight. The rump feathers and others on the body may be erected. Sunning postures may be held for several minutes’ time. As Goodwin (1967) points out, the functions of sunning are obscure, but may include generation of vitamin D through UV irradiation of oil on feathers and stimulating ectoparasites to activity, following which preening or scratching may more readily dislodge them.

The difference between basking in sunlight and postural sunning is not great, and individuals regularly shift into and out of sunning postures. The function of basking would seem to include economic regulation of normally high body temperatures in cold weather, and the importance of basking probably increases in unfavorable conditions. In winter, feral pigeons spend approximately 6 hours at feeding sites in rural Bratislava, and after completing the commute from city centers on sunny days, basking and sunning are undertaken for more than two hours prior to feeding, shortly before mid-day (Janiga 1985c).

G: Preening

This is essentially the same as in other birds except that the preen gland does not seem to be used. On only a few occasions have I seen a preening Pigeon nibble at its preen gland as some passerines and galliformes regularly do when preening. The powder down which permeates the feathers seems to act in lieu of preen oil to waterproof them.

The head and bill are cleaned by scratching with a foot. The foot is brought straight up to the head, not over the drooped near wing as in sandgrouse and many other birds.

If the eye irritates it may be rubbed on one shoulder, a movement shown by many other birds.

J: Preening

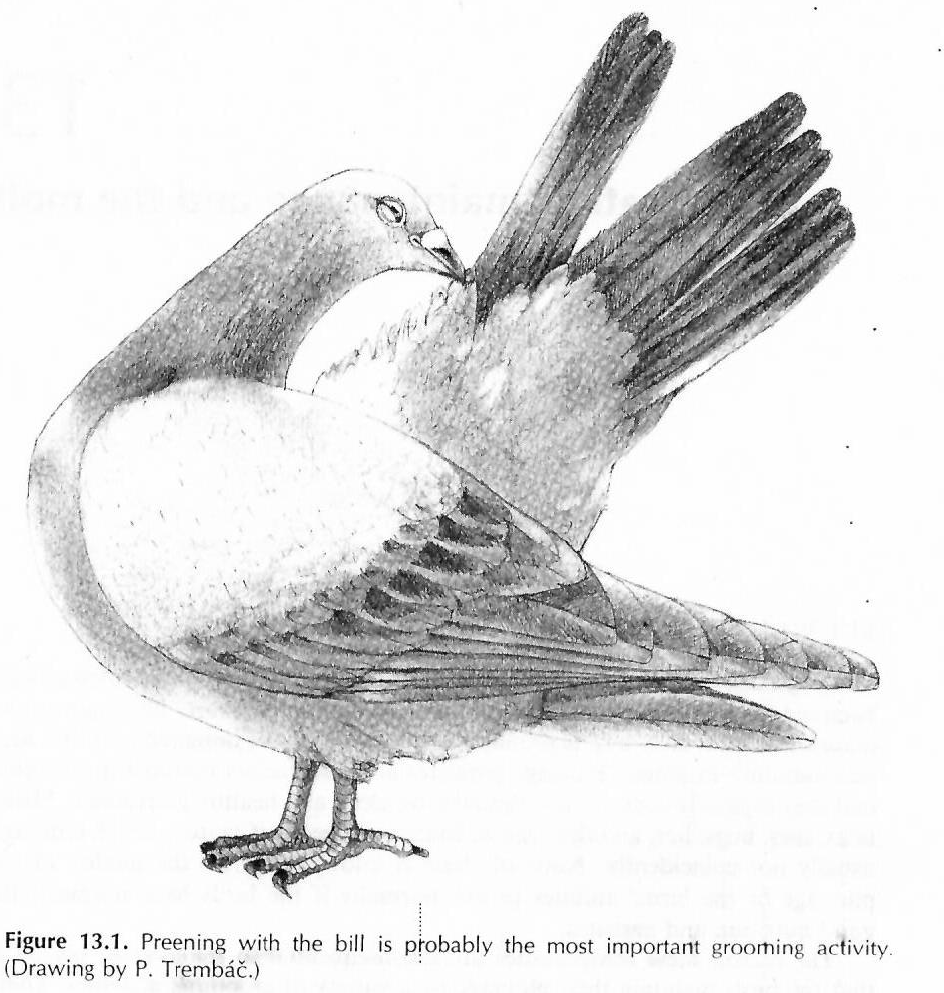

Preening with the bill is probably the most important grooming activity (e.g. Clayton, 1991). In preening behavior, pigeons handle, as it were, a great number of their feathers every day with their bills, nibbling and stroking each feather with the bill tips. This corrects or rearranges the feather vanes, which are important in flight surfaces (especially the remiges and rectrices) and in insulation. They also dispose of any ectoparasites they come across. At the same time, the bird may disperse pigeon down powder over the feathers, which is a help in waterproofing the plumage.

G: Stretching, shaking, and similar movements

A frequent movement is one in which the still folded wings are held vertically above the back at the same time as the head and tail are lowered. In another, one leg is stretched backwards and at the same time the wing on the same side is fully stretched backwards above the leg being stretched and the tail is spread.

A common series of movements is one in which all the feathers of the body are erected, the folded wings held a little away from the body and both wings and body are violently shaken. This is done especially after preening. A lateral shaking or wagging of the tail is often performed after preening or shaking. A sudden lowering of the folded tail and then bringing it back to its former elevation appears to be sometimes to serve to reposition the tail in relation to the folded wings, and sometimes to be a very low intensity flight-intention movement.

Shivering of the body and wings occurs if the bird is very cold, sometimes when it, apparently, feels ill at ease, and sometimes when it is about to die.

In what is similar to but probably not homologous with the human yawn, the bird somewhat stretches its neck and opens its mouth widely. The end half (approximately) of the upper mandible may be lifted above the lower mandible while the mouth appears otherwise to be kept closed.

J: Foot-scratching

Pigeons scratch anterior ventral and dorsal body regions, perhaps as a response to certain ectoparasites such as hippoboscid flies or in freeing feathers that may have become attached to one another in the course of feeding on juicy fruits.

J: Down powder dispersal

Pigeons have powder down distributed generally over the body surface, so in the course of bill-preening they will automatically distribute down powder through their plumage. The powder is a product of breakdown of down feathers and is clearly a feather dressing; it may function to assist smooth imbrication of feathers. Some observers suggest that powder is a waterproofing agent, but, if so, it does not seem as effective as oil in that respect. And, feral pigeons can use oil as a feather dressing, because they have functional uropygial oil glands (Lucas and Stettenheim 1972; Johnston 1988).

G: Roosting

At night a healthy adult Pigeon usually rests on one leg at a time, its foot is more or less centrally positioned relative to the body and the other leg drawn up and hidden in the feathers. Often, and probably always, the relative position of the two legs is changed at intervals. Sick individuals use both legs to support themselves.

The same one-legged posture may be used when resting by day but then resting on both legs, squatting, and lying down cushioned on one wing are also often used by healthy adults as well as by young or sick individuals.

When roosting, or dozing by day, the Pigeon draws the head close into the body, it is never turned and tucked “under the wing” as in passerines and gamebirds.

AGGRESSION, TERRITORY, AND ESCAPE

G: Intra-specific aggression

Serious fights, as distinct from brief squabbles or attacks on unresisting individuals, are usually over nesting territory or (but less often except in over-crowded conditions) roosting perches. Contrary to what obtains in many other pigeons species, fighting is mainly with the bill unless or until the fighting bird is feeling afraid. The head, especially the areas at and around the base of the bill and around the eyes, are the focal points of attack. The eyes themselves appear seldom to be damaged so it is possible that the birds deliberately avoid pecking them, although they do not appear to do so. The orbital skin may, however, be severely damaged. The instinctive fighting movements are adapted to fighting on ledges and attempting to hurl the opponent off of them. The attacker, having got a grip on his opponent, first pulls a little back towards himself, then pushes violently away. If the birds are fighting on a ledge, he tries to force the other off of it. During a fight on a ledge the opposing birds constantly try to get between the opponent and the wall.

Roosting or resting birds maintain individual distance and peck towards and coo defiantly at any others, except their mate, dependent young or siblings with whom they still have a friendly bond, who encroach too near.

Trespassers are always attacked if they do not move off at the first aggressive approach. There is no inhibition against attacking young or (except in some sexual contexts) submissive individuals. If a young Pigeon blunders into a strange nest site, it is ruthlessly pecked in spite of its cowering and squeaking and, if it is cornered, it may be scalped or even killed.

The only exception to this are that some very few individual males (Domestic) show a fatherly attitude towards all fledglings and recently bereaved pairs may adopt strange fledglings.

Fighting over food occurs, but under circumstances that suggest that the Pigeon’s aggression is roused by bothersome trespass on its individual distance. Thus, a Pigeon pecking at a lump of bread or fat, or one feeding from a man’s hand whilst perched on his wrist, will often peck at, and if opposed fight, another that approaches very close or actually jostles it. Possibly under natural conditions isolated seeding heads of plants or small snow-free patches may be similarly defended. Except when food is thus localized no attempt is made to drive other Pigeons, or birds of other species, from food sources. In this C. livia differs from the fruit doves of the genus Ptilinopus. When very hungry Pigeons are feeding from grain or other food that is “clumped” within a rather small area, they often run quickly about, raising and/or half spreading their wings and apparently trying to displace or confuse competitors by pushing sideways against them at the same time. The behavior is very like the wild wing-flapping of hungry, begging, young and seems to be homologous and induced by a similar mood in the birds. One of the functions of the wing flapping of the begging young and its tendency to spread a flapping wing over and “around” the neck of its parent may be to momentarily confuse or exclude its sibling.

G: Territory

Territory has been mentioned as the chief cause of serious fights. The Pigeon’s nesting territory is remarkably compressible or expandable according to circumstances. If a cock Pigeon can successfully defend a large area (though small by comparison with the territories of many tree-nesting species) around his nest site, even a whole cave, shed or barn, he will do so but usually he cannot. Where there are many competitors their persistence and the fact that his fighting drive dies down considerably during the incubation period, usually results in each Pigeon only being able to maintain a small area immediately around his nest. As Pigeon keepers know, judicious arrangements or perches and boxes can result in each cock bird only defending his own box and roosting perch.

Roosting birds at communal roosts usually defend only the space immediately around themselves. If the roost is within the nesting territory the situation is, of course, different.

G: Predator mobbing

Mobbing or attacking of predators seems not usually to occur. There are, however, records of Pigeons (Feral and Domestic), responding to the presence of a flying bird-of-prey in a very stereotyped, and therefore almost certainly innate, way. The birds gather into a fairly dense flock, rise above the predator and then repeatedly swoop down at it, often appearing almost to touch it.

G: Escape and fear responses

Usual, and often consecutive, responses to an approaching predator are: eyeing it anxiously and giving the distress call, “freezing” in either a crouched or erect posture with plumage sleeked down and the wings concealing the white rump patch, and taking wing.

When chased by a bird-of-prey, the Pigeon (Feral and Domestic) flies at great speed, trying to avoid being seized by “last minute” dodging and swerving. In this situation the Pigeon will dive headlong into any suitably sized hole or crevice with a complete lack of any of the caution otherwise shown when entering an unknown cavity. Similar rapid flying and dodging is performed when a Pigeon is chased by a House Sparrow or Spanish Sparrow (Passer domesticus or P. hispaniolensis) but that it is less frightened then is shown by its never plunging into a hole when a sparrow is pursuing it.

Pigeons fear for some days or more any place where they have been frightened. This serves them well in reference to attacks by domestic cats and, presumably, other predators. Fear responses are shown to the sight of a concentration of Pigeon feathers and also, rather surprisingly, to many other conspicuous objects that are unfamiliar and contrast with an otherwise familiar background or substrate. A handful of wheat or millet, dropped down so that it forms a discrete patch, will often scare hungry Feral Pigeons which would eagerly pick up scattered grains.

Pigeons fear gunshots and other very loud and unexpected sounds. If on the ground in the open they usually respond by taking flight but if on ledges above ground they more usually crouch immobile.

G: Species recognition and imprinting

It seems probable that, as in other species, the characteristics of its own species is learnt by the young Pigeon from its parents, shortly before and after fledging. Or there may be innate recognition which is normally reinforced then but which may be obliterated if the young bird is reared under foster parents. Paradoxically there is less information on interspecific imprinting (other than on man) in this species than in some other pigeons. The reason is, of course, because Domestic Pigeons have often been used to hatch and rear the young of wild species in captivity but not vice versa.

Young Pigeons that are hand-reared by man, but in company with others of their species usually behave normally as adults except for often reacting socially and sexually to humans as well as to their own kind. Some Domestic Pigeons that have not been hand-reared but have been handled and talked to by humans from their young days also react socially to man as well as to their own kind.

Pigeons, doubtless through imprinting, prefer to pair with birds colored like their parents. One investigator (Warriner) found that only hen Pigeons were so affected but this is not always the case; I have known clear instances of such sexual preferences based on imprinting in both Rock and Domestic Pigeons. This preference for the parents or foster parents’ color is irrespective of the bird’s own color.

G: The defensive threat display

The bird erects most of its plumage, spreads the tail and raises one or both wings. This display is given when the bird appears simultaneously impelled by conflicting impulses to escape and to attack. It is often seen when a timid Domestic Pigeon (but one not quite timid enough to flee the nest) defends the eggs or nestlings from an intruding hand. The bird usually then lifts the far wing, orients its head toward the human intruder, raises itself, utters loud distress calls, and strikes out with the near wing when the hand reaches the critical distance.

A Pigeon that is less frightened of humans defends the nest against an intruding hand by fierce pecking but with little or no plumage erection and between attacks usually utters the self assertive coo. In a fight with a conspecific, if elements of the defensive threat display such as plumage erection and repeated wing striking with the wings occur, usually the bird so behaving is afraid and will shortly lose the fight. In this point C. livia differs from other species in which beating with the wings in intraspecific fights is shown equally by the more self-confident of the two fighting birds.

From the time they are about half grown, nestling Pigeons may react with essentially similar display if alarmed. They rear up in the nest, in contact with each other, or against the back of the nest cavity or box, erect their feathers, especially those on the neck, make a puffing sound as they inflate and deflate their necks (though not to the same degree as the adult when cooing), make a snapping noise and may lunge, open-billed, at the intruder. Like the homologous behavior of the brooding adult, the function of this is to intimidate a potential nest predator. Young able, or nearly able to fly, will flee from the nest under comparable circumstances but they may give the display if they are cornered in a cage or nest cavity.

G: The bowing display

This has three distinct but often intergrading forms: sexual, self-assertive, and defensive. These terms are not meant to imply exclusiveness of motivation; self-assertiveness is a component of the “sexual” and “defensive” forms of the display and a state of sexual activity is probably a prerequisite for the self-assertive form.

In the sexual version, the male flies up into the air towards the female, claps his wings, alights near her and runs towards her, cooing loudly with inflated neck and feathers of the neck, lower back, rump, and belly erected. On reaching her, he lights his head high. Spreading (and reclosing) and depressing of the tail so that it brushes the substrate accompanies this bowing display, most often, but not always, correlated with the upward movement. Then the male turns in a quick circle, bowing low and cooing, then again lifts his head and turns away. Quick nodding movements are shown during temporary pauses in the display. The male may run around the female, displaying, and is particularly likely to run in front of and then around her if she walks away from him. This version of the bowing display is given by the sexually active male to known females, to strangers of either sex and, but rarely, to males known to him as such. When joining her nest-calling mate on the nest site, the female often jumps towards him in what appears to be a short version of this display. Rarely in Domestic Pigeons I have seen the female display in this manner to her mate immediately after both of them have been involved in fights with neighbors.

As Nicolai (1976) has shown, the circling and clapping above the hen of the domestic breed known as the Finnikin or Ring-beater (Ger. “Ring-schlager”) has been derived, by artificial selection of aberrant performing individuals, from the above display.

In the self-assertive form of the bowing display the bird turns around and around cooing but shows little or no lifting of the head (except in intervals) or spreading of the tail. This display is given by the male, when in reproductive condition, on alighting in or near his nesting territory or in some other familiar place or when (in such an area) he sees another Pigeon especially a stranger or rival, approaching. A male (Domestic or Feral) returning home after being away some time, or re-visiting a former home may display in this manner on alighting even if no other pigeons are in sight; this is the only situation in which I have seen this display given by a bird that is completely alone. Of course pigeons that are reacting socially to humans are not “alone” if the latter are present! The female seldom uses this display except when at her own roosting or nesting site. When she does so, she does not turn in a complete circle but makes a partial turn and then back again through the same arc.

The defensive form consists of merely lowering the head and uttering the self-assertive “oo-roo-coo-t-coo”. Usually the bird doing this faces its enemy but it may turn partly away from it. This display is shown in defiance or as prelude to attack and is not restricted to individuals in breeding condition.

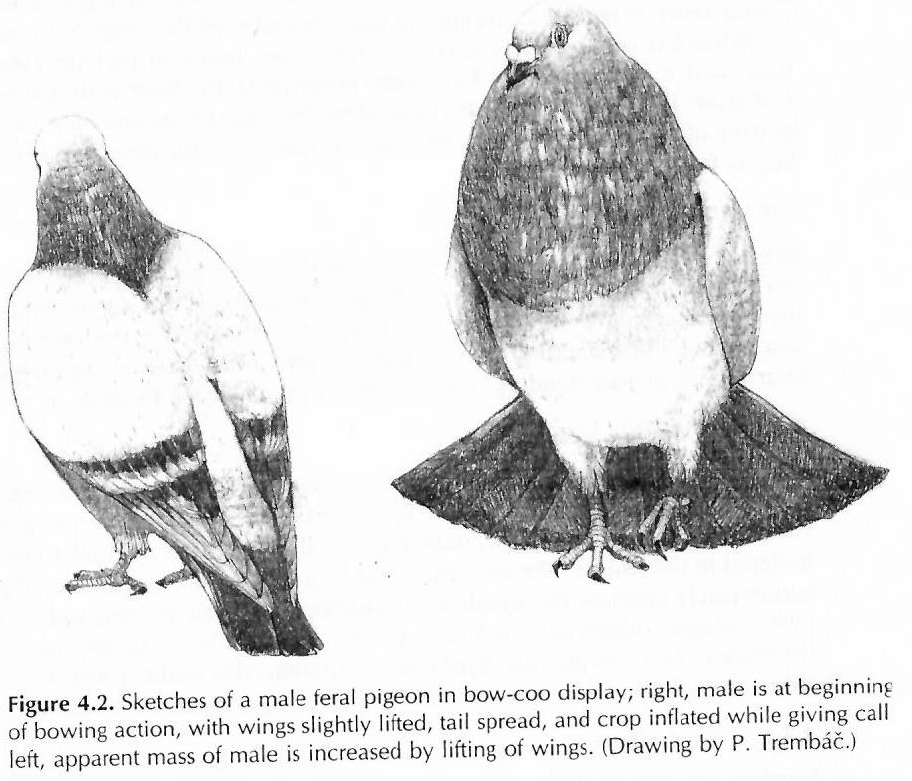

J: The bow-coo

Male Rock Pigeons that are interested in forming a pair will give advertising song, which encourages the approach of females. But, when another bird comes to the territory, the male does not automatically know its sex; the male is consequently ambivalent. An ambivalent male is partly aggressive, and determines the sex of the newcomer by its responses to aggression – another male will tend to be aggressive in return and will be driven off. A female is not aggressive if she is reproductively oriented, and the male sings and dances around her, doing the bow-coo. The vocalization, coo, roo-c’too-coo (Goodwin 1983a), is the song of the Rock Pigeon, and the dance includes the ritualized bowing routine in which the bird stands tall, inflates its crop, and brings its head and neck sharply down while singing. At the same time, it maintains a strutting walk, circling about, periodically fanning its tail. If the female continues to observe the male, he apparently will have passed the several tests of adequacy that females employ. The male continues to bow-coo.

G: The display flight

The bird flies out from the cliff or building, claps its wings several times through a wide arc, then glides with them held above the horizontal plane and tail somewhat spread. Several consecutive clapping and gliding may be performed; the displaying bird may fly in a wide circle back to or near its starting point or go to some other perch. Short distances may be entirely covered using the clapping phase of the display flight and, as has been noted above, a “condensed” form of display flight usually introduces or intersperses the sexual form of the bowing display.

Less intense versions, usually without audible wing claps, may be used by immature and non-breeding birds. In Feral and non-monstrous Domestic Pigeons, a sexually active male commonly performs the display flight in the following situations:

1. When he notices another Pigeon on the wing, especially if it is above him,

2. When he sees his mate or another Pigeon in display flight nearby,

3. When about to alight at or near his home after having been away foraging or after having been taken away by man and forced to fly back,

4. When flying in company with his mate (possibly then also as a response to some of the other stimuli listed above),

5. Immediately after copulation.

The female uses the display flight in the first situation only if she is unpaired and then less often and less emphatically than a male in similar plight. Under the other circumstances listed above, the female may use the display flight if her mate first begins to do so. I have never seen a paired female, in company with her mate, clap and glide unless he first did so.

The mood of the display flying bird seems to be self-assertive and sexual rather than aggressive but sometimes it appears to be elicited by thwarting, suggesting that, at least in such cases, inhibited aggression may be involved.

A main function of the display flight is to advertise the presence of a bird in reproductive condition. Unpaired females are strongly attracted to a male in display flight.

Some domestic breeds show hypertrophy of the display flight. Ring-beaters use the loud clapping flight almost whenever they fly from one place to another (Nicolai); most Pouters and Croppers use it much more freely and at higher intensity than do “ordinary” Pigeons. In these cases it seems that selection for respectively the “ring-beating” and the ability to greatly inflate the neck and the inclination to do so at the very slightest excitation, have resulted in selection also for apparently genetically linked hypertrophy of the display flight. One effect of the latter is that the males of such breeds as Ring-beaters and Step Pouters soon wear and fray their longest primaries through constantly beating them violently together in display flight. As Nicolai remarks, the resultant greater vulnerability to birds-of-prey and greater energy needed for flights to distance feeding grounds have doubtless curbed any such tendencies to excess in the wild form. Indeed some, and possibly all, pure wild Rock Pigeons use display flight less intensely, tending to clap their wings less violently and to glide with them less highly lifted than even most Feral Pigeons do. Nicolai tells me that some Ice and Starling Pigeons (two wild-shaped European breeds of Domestic Pigeons) display fly in the same manner as Rock Pigeons and a male Ice Pigeon that I once owned used to perform the gliding phase of his display flight on more or less horizontal wings almost like a Wood Pigeon, Columba palumbus.

Nicolai is of the opinion that the rolling and tumbling of Roller and flying Tumbler Pigeons has derived, under human selection for such aberrations, from the display flight. His evidence, based largely on the ontogeny of the “rolling” of Birmingham Roller and the behavior of crosses between Rollers and other Domestic Pigeons is convincing.

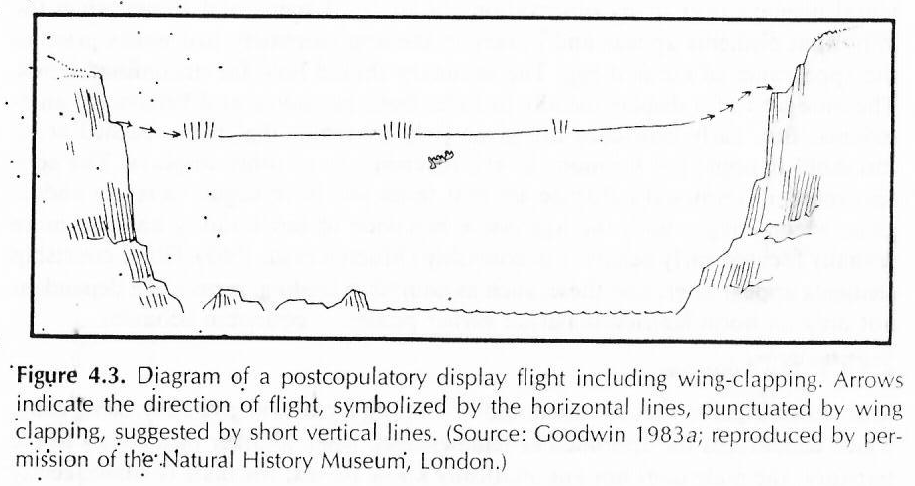

J: Postcopulatory display

Following a copulation, the birds move apart and may preen some of their feathers. The male may stand tall and then launch into a display flight, perhaps circling 30 to 60m, periodically clapping his wings. In this action, the wings are brought unusually high on the flight upstroke and the primaries and manus of each is smartly slapped together three or four times. A male may have two or three rounds of clapping in a flight covering perhaps 40m.

The rituals of pair formation are repeated each time the pair has a clutch of eggs, although the amount of time involved for the renesting pair is much shorter than for individuals forming a new pair. Ritual repetition seemingly is necessary to entrain the complex series of endocrine releases that ensures the sexes are physiologically and psychologically synchronized for egglaying and incubation.

G: The wing-lifting display

In this display, the folded wings are lifted and held in about the same horizontal plane as the back; often the bird walks a few paces or turns partly around with them in this position. In a wild-colored bird the black bars across the light bluish gray wings and the white patch on the lower back, which is precisely “pointed to” and framed by the converging black bars, are prominently displayed to any creature above. This display is given by males (and less often and usually at lower intensity by females) in reproductive condition in response to the approach of a conspecific from above, and usually also from behind. It probably originated as a flight intention movement (and may at times immediately precede taking wing in a display flight) but now serves to display the wing markings and inform the bird at whom it is directed to the displayer is a conspecific in breeding condition. Some other pigeons with conspicuously marked wing coverts, for example the Diamond Dove, Geopelia cuneata, have homologous and similar displays.

G: Nodding

A downward movement of the head, at the lowest point of which the bill makes an angle of about 85-90 degrees to the horizontal, is given under the following circumstances:

1. By both members of a pair when at the nest site or when coming together again after a short parting,

2. By a female in response to sexual, self-assertive or even aggressive behavior from a male with whom she wishes to pair,

3. By a bird alone on the nest site but with its mate or a prospective mate nearby,

4. By a bird threatening another, usually in defensive context.

In all of the above circumstances, nodding is usually interspersed with sexual, self-assertive, aggressive, or defensive behavior.

Comparison of the nodding of this species with that of other pigeons, in some of which it is less definite but in others of which the downward nod sometimes or usually culminates in the movement made when fixing a twig into the nest, suggest that nodding is derived from nest building movements. The one factor common to all situations in which nodding is used is that the bird appears determined to “hold its ground” and stay where it is, in spite of any opposition. Probably the mood of the nodding bird is very different in different contexts and the information conveyed is considerably modified according to the context in which it is given and the status of the receiver.

G: Displacement preening or ritual preening

In the usually form of this movement, the bird turns its head, thrusts its bill between body and scapulars, and quickly withdraws it. It is given by the male in situations where he is sexually aroused but unable to copulate or commence the pre-copulatory billing either because the female is not yet giving the appropriate signals or because of his own apparent incapacity. That the same gesture is used in these apparently different situations suggests that it is being used whenever an impulse to bill or to copulate is being frustrated but no other positive tendencies – such as to flee or to attack – are present. It also corroborates Whitman’s (1919) opinion that this act provides auto-erotic stimulation as well as serving as a signal to the mate. It is also an integral part of the ceremony of offering to bill, which male performs before proffering his open mouth to the female.

The female does not usually displacement preen so much as the male. This is because she reacts to sexual unreadiness on her mate’s part by more intense soliciting of billing or coition, by “switching over” to allo-preening him or, if the male crouches and invites her, by mounting him instead. She will, however, displacement preen freely and often if thwarted in her sexual desire and unable to find outlet in the alternatives usually shown. Thus a hen Pigeon who considers herself paired to a human being will displacement preen as much as or more than a cock usually does.

Some males (possibly all) also displacement preen at the side of the breast, much as does the Black-headed Gull, Larus ridibundus. This may alternate or be interspersed with the usual “behind the wing” movement. It is not always possible to draw an absolute line between displacement preening behind the wing and real preening in this area. If a Pigeon that is engaged in preening is very slightly sexually aroused by the arrival or sexual behavior of another, it will often preen behind its wing. It then uses the normal movements not the ritualized form but its subsequent behavior usually suggests that sexual impulses had caused it suddenly to pay attention to this area.

The function of displacement preening seems to be to indicate the performer’s sexual and peaceable intentions and to arouse a similar mood in the partner.

G: Wing twitching

A sharp spasmodic twitching or jerking of the folded wing is given both in defensive threat and when nest calling, in either case it usually intersperses vocalizations or more positive movements. Visually, in the present species, the most noticeable results is a short, sound-producing, upward twitch or jerk of the folded primaries. These wing movements seem to be homologous with, although much less intense than, the wing movements of begging young. If the male or foe is on one side, only the wing nearest to it is twitched, if it is in front then the performer twitches both wings at the same time. Other species have homologous wing movements, in some of them these are elaborated so as to exhibit bright wing markings when nest calling, in others they are combined with or replaced by lifting and/or spreading of the tail. In many species the wing movements are shown in similar tempo to those of normal flight.

As with nodding, this display can appear conciliatory or hostile according to context. Perhaps in both contexts, and even in the food begging of the young, there is an element of thwarted or sublimated aggression.

G: Nest-calling

When a Pigeon seeking a nesting place, together with or in view of its mate finds a possibly suitable site, it adopts a crouching posture with tail and rump somewhat raised, lowers its head and calls repeatedly. The calling is often accompanied by nest-shaping movements in which the bird partly rotates or moves from side to side and makes outward scratching movements with its feet on or in the substrate. The call used is similar or identical to the normal advertising coo, at least to human ears. Both sexes nest-call but usually the male does so more often and at higher intensity than the female. This is simply because he usually takes the lead in finding a nest site or in returning to one already selected. Exceptionally lone Pigeons in full reproductive condition may nest-call but usually this behavior is only shown when the mate or a prospective mate is in sight nearby. The opinion to the contrary held by some laboratory workers has undoubtedly often, and perhaps always, been due to their captives responding sexually to them. Nest-calling is shown most intensely by newly paired or pairing birds at a newly found nest site but it precedes every nesting of a pair and, to some extent, may extend into the building period. The amount of nest calling is, however, usually less with a well established pair at a site where they have bred before.

When the bird has joined its mate on the nest site, allo-preening of the calling partner’s head, mutual calling or, more often, alternate calling from whichever bird has temporarily insinuated itself into the central part of the site, and wing-twitching occur. As has been said, the female may initially come up to the nest-calling male in an abortive-looking version of the bowing display. She may at that moment peck her mate’s head quite roughly (and less often he may roughly peck her when she is nest-calling) but a nest-calling bird is never put into an aggressive mood by such treatment; it merely pushes its head under the other bird’s breast. This hides its head, always the focal point of attack in this species, and also simulates the posture and movements of a squab pushing under to be brooded after its parents have fed it. Nest-calling and associated behavior appear to involve very intense emotion and to play an important part in cementing emotional bonds between the two birds performing it together.

G: Allo-preening (or caressing)

This consists of a gentle-looking nibbling movement of the bill, which is thrust into and moves about among the partner’s feathers. Frequently the bird will seize some minute object in its bill tip and either swallow it (the throat movements clearly visible) or (less often) cast it away. Although it may briefly treat other parts of the partner’s body in this way, the allo-preening bird usually confines its attentions to the other’s head and nape. At least 99% of all allo-preening is in these areas which the bird cannot reach with their own bill. These areas are approximately (but not exactly) those above and on the upper periphery of the modified display plumage on the neck. Allo-preening is usually performed gently but the allo-preening bird may be rather rough at times and, even on an observational level, it is difficult to say where aggressive picking ends and caressing begins.

Usually allo-preening takes place only between members of a mated pair, less often between other mutually friendly individuals. The bird actually being preened often moves its head about as if trying to avoid the other’s attentions. This is especially the case with dependent young that are caressed by their parents.

I believe that one function of allo-preening is to remove ectoparasites and perhaps also other foreign bodies from the preenee’s head. It also appears to divert aggressive impulse that are, or seem likely to have been, aroused and then thwarted. Although allo-preening of the partner is shown in such circumstances, I do not think the Pigeon caressing its mate or young is usually in the same mood as one about to attack or about to copulate. On sexual and aggressive tendencies have been (temporarily) sublimated. The allo-preening partner may, however, be rough on occasions. In juvenile Pigeons, especially siblings, one often sees aggression “switch over” into allo-preening.

J: Hetereopreening

When it is evident that the female is willing to consider the male’s proposal further, the male comes closer to the female and ultimately begins to bill her head and neck feathers. The action looks like simple preening, but it is probably not functional grooming. Such preening certainly is a major step toward bonding, however, as it involves non-aggressive contact between the two individuals. When the female finds heteropreening satisfactory, she preens the male in return. The process of pair-formation is now underway; it may remain at this point for a day or two. In this period, the male occasionally flies to the spot he thinks is good for a nest (or to an actual nest, if one already exists), demonstrating it to the female. This activity is repeated throughout the remainder of the courtship routine.

What has occurred will have required a few hours on perhaps two or three days, and it will frequently have been interrupted by other activities – going to and from the feeding grounds, time spent feeding, intrusions of other pigeons, passing of potential predators, and the like. Each time the courtship is renewed, it begins from the beginning.

G: Billing

This, in its fullest form, consists of the male offering his open mouth to the female, immediately after having made one or more displacement preening movements behind the wing. She then inserts her bill into his mouth and is fed by him as a fledged young bird would be. I have seen this form of billing rather rarely and always with Feral Pigeons not with Domestic Pigeons. With the latter, and often also with Feral Pigeons, the male appears not to disgorge food. He does, however, make movements as if regurgitating and the female may make similar movements while their bills are together. The female also usually makes swallowing movements of the throat but, unless she swallows small amounts of liquid, it is certain that in many cases nothing is passed from one bird to another.

I have not seen this behavior in Wild Rock Pigeons sufficiently close to know whether actual feeding of the female may more frequently accompany billing in the wild state. In all its forms, billing is usually the prelude to copulation; it is followed by the female crouching to invite coition and the male mounting her.

G: Courtship feeding

The male eventually responds to begging routines by feeding, or seeming to feed, the female. He opens his bill, the female inserts her bill into the upper part of his throat, the male begins regurgitating material from the crop, and transfers the material to the female. The material might be a seed, or it might be crop fluid. The action rarely provides the female a real feeding (although Murton and Westwood (1977) suggest otherwise), such as is given to squabs, but is perhaps an index to the male’s ability to provide. Early in a courtship, this point is where the action stops. In mid-courtship and later, it is followed by copulation of the pair.

J: Begging

Begging is done by the female, pecking lightly at the male’s bill or face near the bill (billing), while shifting her near wing repeatedly up and down, which resembles food-begging by a squab. This behavior occurs when the two birds have reached an understanding of one another and when each is approaching the later phases of pair-bonding, which begins with courtship feeding.

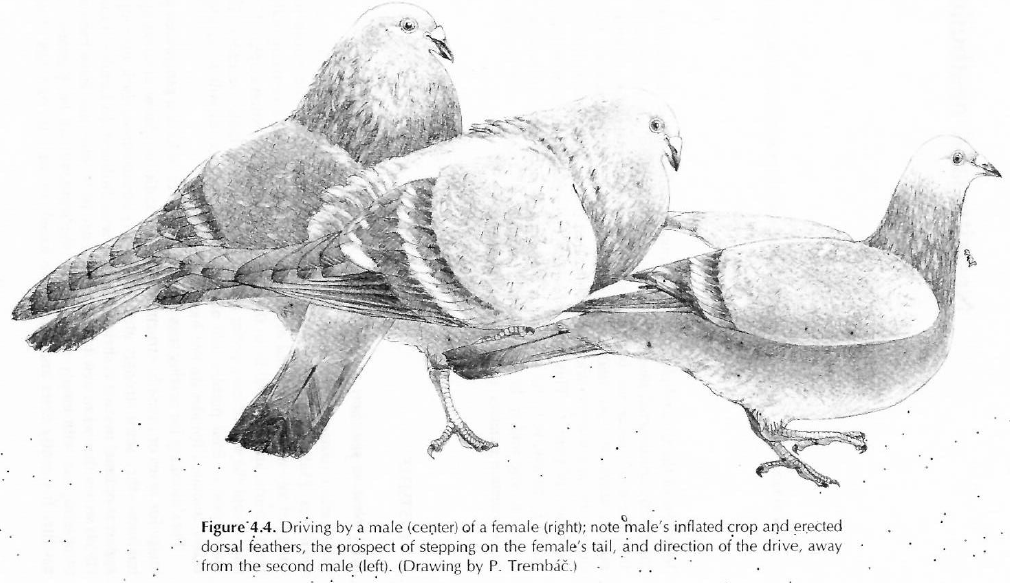

G: Driving

This term is used for the behavior shown by a male Pigeon to force his mate to move away from the proximity of other male Pigeons or, but less often, from some place in which he feels afraid of ill at ease. The object of driving has often been misinterpreted owing to the Pigeons studied being in crowded lofts or small cages in research institutions, not in complete freedom. Another source of error has been that some German ornithologists use the term “Treibin” for driving (as here defined) and others use it for the sexual form of the bowing display.

Driving occurs during the period that the female is sexually receptive. It is very noticeable in Domestic Pigeons kept in flocks but can be seen wherever wild Rock Pigeons or Feral Pigeons gather at some common feeding ground, during the breeding season. When driving intensely, the male follows his mate everywhere, often literally “treading in her tail”. He pecks, usually gently but often quite fiercely, at the back of her head. If she takes wing he flies closely behind and above her. If the female goes to a distance of about thirty yards or more from other Pigeons, the male usually stops driving. If she flies to a ledge or roof where there are no others, he almost always stops. It is only in the crowded pigeon loft or aviary that the male Pigeon really “drives to nest” and continues to harry his mate until she enters their nest box. If she approaches other Pigeons, or they approach her, the male begins to drive by getting between his mate and the others, thus forcing her away from them.

Driving does not usually take place if there are no other Pigeons nearby. Of course, a male Pigeon that is reacting socially to man will often begin to drive his mate when a human approaches them. Also, a male Pigeon may try to drive his mate from any place where he feels afraid; this may also result in driving when approached by a human. Driving appears to be a form of aggression, usually (but not always) motivated by sexual jealousy.

Some (possibly all) other species of Columbidae also show driving behavior, as do many other birds. I think that the function of driving is to remove the female from the vicinity of potential sexual rivals. It prevents her being fertilized by other males and gives the pair opportunities to copulate without interference. Its (relatively rare) use in other situations is probably a fortuitous result of their eliciting similar feelings in the male to those aroused by the presence of sexual rivals. Under conditions where the female cannot get to any place where the male feels at ease with her or where she must closely approach males other than her mate to obtain food, she may be injured or caused to partially starve by the driving male. Such pathological results of driving never occur under natural, or even semi-natural, conditions.

J: Driving

Subsequent to pair-bonding, the pair tends to be a unit and do things together. This may be a result of the male closely attending to the female, which may reasonably be called mate-guarding, and it is a feature of the reproductive behavior of many species, especially those in which extra-pair copulations are known to be regular in occurrence. At a variety of times prior to egglaying, the pair will come into close proximity to unattended males, and these are inevitably attracted to females. A mated male will then closely escort his mate beyond some ill-defined border away from other males; he does this by what has been called “driving”, which fairly describes the intensive herding of the female by the male. The male is for the most part afoot, interdicting other males and redirecting his mate from them, but when the female take wing, the male very closely accompanies her. Thus, the picture presented by driving is a hurried herding by one bird of another, punctuated by occasional flights, some of which may be only a meter or so in extent. Females often retire to the nest site, especially when it is reasonably close. Males tend not to stop driving until other males are at some distance from the female.

G: Copulation

Typically, copulation is preceded by bowing display from the male and nodding and other sexual responses by the female. Its immediate introduction is by the male holding himself with neck upright, displacement preening behind the wing, and offering his open mouth to the female. Billing follows, perhaps repeated two or more times, and then the female crouches with retracted neck and folded wings held slightly out from the body so that the male can perch on her humeri. After making intention movements of so-doing the male jumps onto the female, makes one or two lateral movements of his tail, then, maintaining partial balance with flapping wings, slides down to one side of the female, puts his tail under hers so that their cloacas are momentarily in contact, and ejaculates. The soliciting female, as can be seen when a hen Pigeon who is responding sexually to her owner solicits him, raises her vent feathers so as to expose her cloaca, whose lips make a rapid opening and closing movement. Immediately after copulation, the male dismounts, both sexes walk a few steps in much the posture of the displaying male in the upright phase of the bowing display and then the male takes wing in a display flight, followed by his mate. At least, in Domestic or Feral Pigeons, the display flight may be omitted and reversed copulation in which the female mounts the male may follow.

J: Copulation

Copulation of the individuals of a pair occurs after the bond is firm, which requires at least a week or more (cf. Fabricius and Jansson 1963; Murton and Westwood 1977). Following a feeding, the female crouches and spreads her wings very slightly, providing a platform on which the male stands; the male mounts, balancing with raised wings, and angles his tail down and to the side; the female angles her tail up and to the side, cloacal union is achieved for a second or two, and spermatozoa are transferred from male to the female. A female’s eyes are usually closed (Sengupta 1974). Females can be the initiators of copulation, but usually it is males (Dorzhiev 1991). The pair copulates fairly regularly prior to and during nestbuilding and for at least a week prior to laying of the eggs.

G: Interference with copulation

Copulating pairs are very often interfered with by others. With rare exceptions these attacks are made only by males that are in breeding conditions. Such a male will often be seen to “get ready” to interfere if he notices a pair indulging in pre-copulatory behavior but he never (so far as I have seen) actually attacks until the other male mounts the female. Then the interfering bird runs or flies at the copulating pair, dislodges the mounted male and begins to peck the female’s head. If the female remains crouching he may (if not by now involved in a brief fight with her mate) mount and copulate with her but this does not often happen. When the female rises he usually stops pecking her and performs the bowing display. If several males attack a copulating pair simultaneously (as often happens where large numbers or males are present in a small area) some or all of them may chase the female for some moments, pecking at her head as they do so.

Thus, the behavior of the interfering male is similar to that of a very “fiercely” driving male towards his own mate and it is, I believe, part of the same behavior complex as driving. As has been said, the latter serves to prevent the bird’s own mate from being inseminated by another male. Since driving is shown more intensely according to the degree of sexual interest other males show towards his mate, one may suppose that the highest possible stimulus for it would be the sight of another male actually copulating with her. In such a situation, only an immediate response might be able to remedy matters. A male who paused to make quite sure that his mate was involved could never interfere in time. Hence, natural selection seems to have favored males that showed an instantaneous aggressive response to the sight of any others of their kind copulating. That this is the correct explanation is suggested by the behavior of the interfering male towards the female of the copulating pair; his apparent “indignation”, his ferocious pecking of her head, and his desisting and displaying to her as soon as she rises, and, presumably, he then sees that she is not his mate. The driving of a female which may occur when more than one male interferes at once seems due to each bird being then too occupied trying to force the hen away from the others to recognize her.

Female Pigeons have been recorded making similar attacks on copulating pairs but I have only once seen a female do this and she was homosexually paired at the time. Young Pigeons often show considerable interest in and closely approach pairs that are performing pre-copulatory behavior. Sometimes they give the grunting alarm when the pair copulate but I have never seen them show aggression.

REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOR

G: Pair formation

Pair formation may proceed quickly or slowly according to circumstances. Sometimes a pair of young birds, often siblings, are attracted to one another before they are sexually mature and indulge in a good deal of at first rather abortive sexual behavior on and off for some months before they appear definitely paired. On the other hand, a pair may form in a matter of minutes if a compatible male and female are in full breeding condition when they first meet.

In free-living Pigeons the female is usually first attracted to the male by his display flight and/or by his giving the bowing display at her. She then responds to the latter by nodding. Billing, copulation, and post copulatory display flight (or other post-copulatory behavior patterns) soon follow. It is not usually until after this that the male goes to his nest site and nest-calls. If, as is often the case, pair formation has taken place before the male has a nest site, the pair go seeking one together, the male taking the lead.

If Pigeons have been kept unpaired until they are at a very high pitch of reproductive condition and a compatible cock and hen are then put together, parts of the normal sequence of actions may be omitted. The hen may crouch and invite coition as soon as the cock begins to display. The cock, if he has a nest site near at hand, may respond to the presence of the hen by going at once to his nest site and nest calling.

G: Nest site selection

Rock Pigeons nest on ledges in caves or potholes or in holes or crevices in the cliff face, less often on sheltered ledges on the cliff face. Feral and Domestic Pigeons more often use man-made (buildings or nest boxes) equivalents to the natural cave and cliff sites. Domestic Pigeons have been proved (Levi, 1969) to prefer sites in semi-darkness and circumstantial evidence indicates that Rock and Feral Pigeons share this preference.

When seeking a nest site, the pair usually go together, the male taking the lead and being the first to investigate possible sites. Unpaired cocks in reproductive conditions will, however, also investigate and claim potential nest sites. They do not, however, usually actively search for one until paired. Caves and cliff holes, and comparable features in buildings, appear to be recognized as such at a little distance through their dark openings contrasting with the immediate surroundings. I have often noticed Feral Pigeons mistake a dark shadow or patch on a wall, that only looks like a hole from a distance, and approach and investigate it. Here similar lighting effects evidently mislead both human and avian eyes.

Having found and entered a possible site, the male begins to nest-call (q.v.) and is joined at the site by his mate.

G: Nesting

When the nest site is decided upon, both sexes may bring pieces of material to it. Serious nest building only starts when the hen remains crouched in the nest site and the cock responds by seeking nest material and carrying it back to her. Twigs, thin roots, and stems of a tough and “wiry” nature are preferred. They are usually sought on the ground and fairly near to the nest site. Wild Rock Pigeons, for example, usually seek nesting material in the immediate vicinity of the cave or hole where they are building, although they fly further inland to feed. I have on a few occasions seen Feral Pigeons collect dead twigs from the outer canopies of conifers growing near the nest sites under railway bridges.

The collecting male pecks at and often lifts and then discards many twigs or stems, when he finds one to his liking, he flies with it to the nest. If the site permits, he gets behind or alongside his mate and gives it to her over her shoulder but does not usually walk or jump onto her back to do so as do the males of tree-nesting species of pigeons.

The female arranges the material, pushing it down around or underneath her. When fixing it in position, she uses a quivering or shuddering movement as do other pigeons and most passerine birds. Nest building seems not completely emancipated from its possible origin as a substitute activity. If during incubation the female is unwilling to quit the nest when the male comes to take over, he may respond by going and collecting a twig. Nest building usually ceases after the second egg is laid but if the nest loses most of its material without losing the eggs or young, either cock or hen may respond by bringing quantities of material for its sitting mate to build into the nest.

The size of the nest depends on the amount of pre-laying time the hen spends on the nest site prepared to build and the availability of suitable material; the first being of course partly dependent on the amount of time needed to find food. The nest is fairly firmly constructed when suitable materials are available. Nests that consist only of “a few straws placed round the eggs”, as books often describe the nests of Feral Pigeons, are usually due to the rarity of suitable material for some Feral Pigeons in towns or their having to spend much time looking or waiting for food.

J: Nestbuilding

Nestbuilding begins about 5 to 7 days after the first copulation (Dorzhiev 1991). During nest construction a pair copulates five to seven times a day, one or two days before egglaying the rate drops to two or three times a day (Kotov 1978).

Active building is ritualized: with the female sitting on the nest site and giving the nest call, the male flies out, searches for nesting material, returns, and gives the material to the female. He frequently stands on her back when transferring the material. The female tucks the material around her breast or flanks, and the male goes for another piece. The male may repeat the procedure 1 to 5 times per minute, depending on how far he flies to the source of material. Nesting bouts last from 5 to 20 minutes, frequently in the forenoon, for 3 to 4 days.

G: Egg laying and incubation

Two eggs are the normal clutch. There are rare instances of one-egg clutches in Domestic Pigeons.

The first egg is laid in the evening, the second in the early afternoon of the next day but one; thus there is an interval of about 43-44 hours between eggs. The hen usually sits on the nest for much of the day before laying the first egg, building with material brought by her mate. While laying, she stands in a penguin-like position, straining and sometimes uttering distress calls. The laying of the first egg of her life appears to cause pain and the egg when extruded is usually soiled with blood. Subsequent eggs are laid with less apparent effort and suffering.

The pair sit (in turn) in the nest from the time the first egg is laid but incubation usually begins with the second egg. When incubating the parent with its bill more or less arranges the eggs side by side, one in front of the other relative to the parent’s position, erects its feathers in such a way as to expose the bare skin of the brood patch (which in pigeons is not modified to anything like the extent of those of species which lay more or larger eggs), and then settles down on them with the rock, side-to-side movement common to pigeons, passerines, and gamebirds in this situation. The eggs are then in contact with the bare skin and surrounded by feathers. If an egg gets displaced on to the rim of the nest, the bird will hook its bill over it and pull it back into the shallow central depression of the nest.

The hen incubates from early evening or late afternoon until about mid-morning of the following day, the cock for the remainder of the daylight hours. Either parent will go to the nest and incubate “out of turn”, if it sees its mate away from the nest or if it sees the eggs exposed. During incubation, feces are retained; the female deposits a very large mass of feces shortly after being relieved from her long session. Very shortly, after an egg hatches, whichever parent is on the nest picks up the eggshell in its bill, carries it away from the nest, and drops it. In some Domestic Pigeons, this behavior is not always shown. Eggs which fail to hatch are not removed.

G: Care of the young

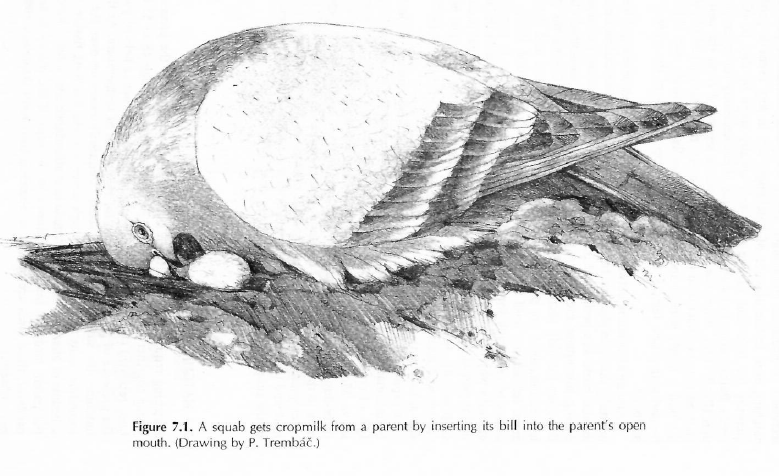

While the young are small, they are kept warm by brooding. Essentially the brooding behavior is similar to incubation although the brooding parent is usually in a different, less prone position on the nest. Young are fed within a few hours of hatching. The parent takes the squabs soft bill into its mouth and regurgitates pigeons’ milk, which the squab gulps down. Two young may be fed at once, each having its bill at either side of the adults’ mouth. As they grow, they usually thrust and push too vigorously to be fed at once. Pigeons adapt their diet to the needs of their growing young, taking more mineral matter and animal food than at other times, and, when the young are small, taking small seeds in preference to peas, maize, etc. This behavior is prevented or distorted when the parents have to compete with others for a limited amount of food or for food only available for a limited time.

When feeding young more than a few days old, the parent disengages its bill, pauses and then offers its open mouth again two or more times in any one feeding session. This functions to allow both young ones, at least if both are strong and vigorous, equal opportunity to feed.

Until the young are well feathered, any others of approximately the same age that are placed in the nest are usually adopted, even at times if they are very different in appearance. Once their young are well feathered, the parents recognize them as individuals and will usually attack strange young of similar age.

If the parents nest again before the young of the first brood are independent (as they often do), the cock continues to feed them until the next clutch hatches or shortly before. Under natural conditions, the father continues to feed his young for some time after they can fly. They follow him to his feeding grounds, where they note what he, or other adults present, are feeding on. This learning to feed from parental example can be (and often is) shown at an earlier age if food is placed near the nest so that the young, while still on the nest, see their parents eating. When re-nesting, Pigeons try to find a new nest site, either near to or at a little distance from the previous nest, where the fledglings may still be. If they are unable to do so, they will build again on the old nest, very often much incommoded by the fledgling when they do so.

Even after they are capable of flight, the young of the previous brood, at least in Domestic and Feral Pigeons, may spend much time standing near the incubating parent if it has used the same or an adjacent site. They are tolerated until the young hatch but, when she sees the newly-hatched squabs, their mother fiercely attacks and drives off the older young if they are beside her. This seems simulated by the sight of the babies as at nests in complete darkness, I found the young of the previous brood often beside the nest (Feral Pigeons) unharmed with their mother brooding the young squabs upon it.

REFERENCES:

Dorzhiev, T. Z. (1991). Ekologiya simpatrickeskikh populyatsii golubei. Nauka, Moscow.

Fabricius, E. and A. M. Jansson (1963). Laboratory observations on the reproductive behavior of the pigeon (Columba livia) during the pre-incubation phase of the breeding cycle. Anim. Behav. 11, 534-547.

Gompertz, T. (1957). Bird Study 4, 2-13.

Goodwin, D. (1955). Bird Study 3, 25-37.

Goodwin, D. (1970). Pigeons and Doves of the World. British Museum (Natural History). London.

Goodwin, D. (1983a). Pigeons and Doves of the World. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

Heinroth, O. and Heinroth, K. (1949). Z. Tierpsychol. 6, 153-201.

Kotov, A. (1978). Data on the ecology and behavior of the Rock Dove in the southern Urals and western Siberia. Byull. Moskovsk. O-va Isp. Priordi, Otd. Biol. 83, 71-90.

Levi, W. M. (1969). “The Pigeon”. Levi Publishing Inc. Sumter, S.C.

Murton, R. and N. Westwood (1977). Avian breeding cycles. Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Nicolai, J. (1976). Z. Tierpsychol. 40, 225-243.

Sengupta, S. (1974). Breeding biology of the blue rock (domestic) pigeon, Columba livia. Gmelin. Pavo. 12, 1-12.

Simms, E. (1979). “The Public Life of the Street Pigeon”. Hutchinson, London.

Murton, R. and N. Westwood (1977). Avian breeding cycles. Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Warriner, C. C. (1963). “Early Experiences in Mate Selection Among Pigeons”. University Microfilms, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Whitman, C.O. (1919). Posthumous works, Vol. III. “The Behavior of the Pigeon” (H. A. Carr ed.). Carnegie Institution of Washington Pub. No. 257